In the US, the early wave of Silicon Valley disruptors — Intel, HP, Compaq — rose just when their East Coast counterparts — DEC, NCR, IBM — declined. And then you have Google and Facebook and others that have become the darlings of today’s internet world.

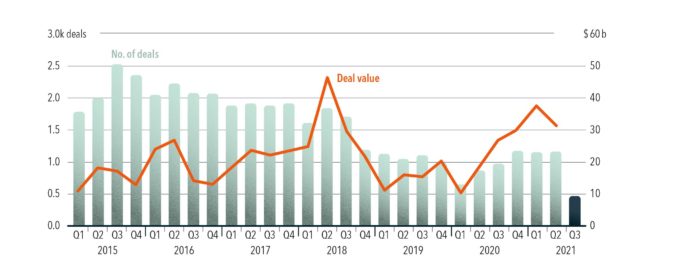

From this view, commentors argue that the crackdown on China’s tech giants is a good thing. First, the funding for early-stage Chinese start-ups has not slowed. Consider the graph below showing the total number and value of VC investment among Chinese start-ups, as reported by The Information. In recent months, some $9.3 billion poured into 470 China-based start-ups.

The policy implication is that VC money is moving away from e-commerce, ride-hailing and online entertainment. Instead, deal flows are going into semiconductors, biotechnology, and industrial robots, where commercial risks are higher and require “patient”, or long-term, capital. The net result of the crackdown is the resetting of China’s VC industry. Venture capitalists will channel more funding toward sectors that the late-stage private equity or stock market can’t serve.

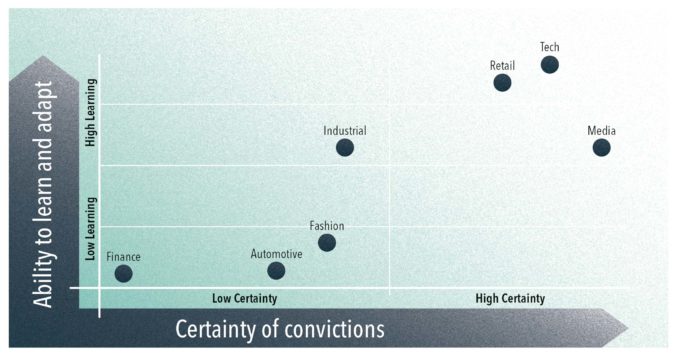

The unintended consequence of the crackdown on tech giants therefore, is funneling new growth to the underdogs. It’s leveling the playing field. Twenty years ago, when Alibaba and Tencent were still in their infancy, software and internet companies were a high-risk, high-reward endeavor. Today, software investment is mainstream. Without some external shocks, money will always go into the more predictable, high-payback projects and thus deprive new areas that are ready to take off once supplied with capital.

So, there you have it: two completely opposing viewpoints that are equally compelling. What this exercise highlights is the impossibility of predicting the exact outcome of key events. For investors, that’s when they diversify and don’t make one single bet. That’s also why smart companies always create options, not just to hedge but to capture the outsized upswings.

Audio available

Audio available